Los Angeles’ Measure M envisions a long list of public transportation improvements throughout the County. Among them is the West Santa Ana Branch, a proposed light rail line which would run between Downtown Los Angeles and Artesia. The 18-mile trip would occur in approximately 33 minutes.

Though not as flashy as the Purple Line Extension, it is probably the most deserving of careful discussion, since its alignment is still undetermined. While most of the route is planned to follow a former Pacific Electric right-of-way, the WSAB could take a number of paths through Downtown, and there are options on the table for the Downtown stations. It is critical to choose an alternative that maximizes ridership and minimizes cost.

Right now, the cost projections are worrying, though not so much as to warrant canceling the extension. As Urbanize previously reported, the estimated price tag is between $3.5 and $4 billion dollars, projected weekday ridership is 75,000. This represents a cost of $50,000 per rider, which is marginal: light rail lines in the United States tend to cost around $40,000 per rider, and much higher costs are difficult to support; within Europe, the cost range is even lower, about $10,000 per rider on many lines. In reality, the budget includes a significant estimate of future inflation, so its value today is likely to be somewhat lower, but the projected capital expenditure per rider is still on the edge of cost-effective.

However, one silver lining comes from the construction timeline. The original plan calls for the line to only open in full by 2041, but Mayor Eric Garcetti's 28 by 28 plan proposes to accelerate the WSAB’s completion date to 2028, in time for the Summer Olympics. Garcetti’s proposal provides no new cost estimates, but as construction costs tend to increase faster than inflation over time, noticeable if not game-changing cost savings are likely.

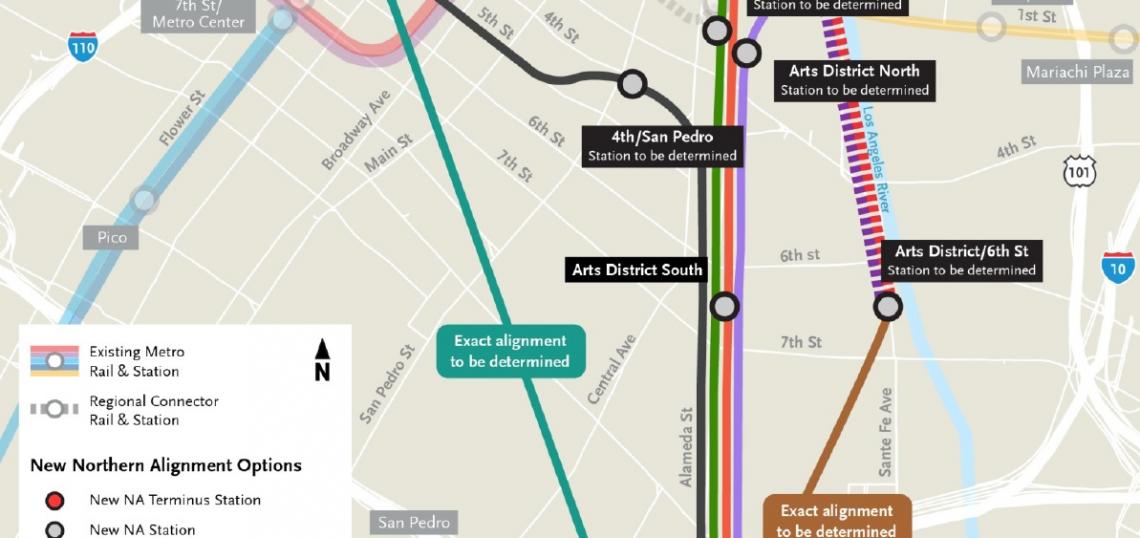

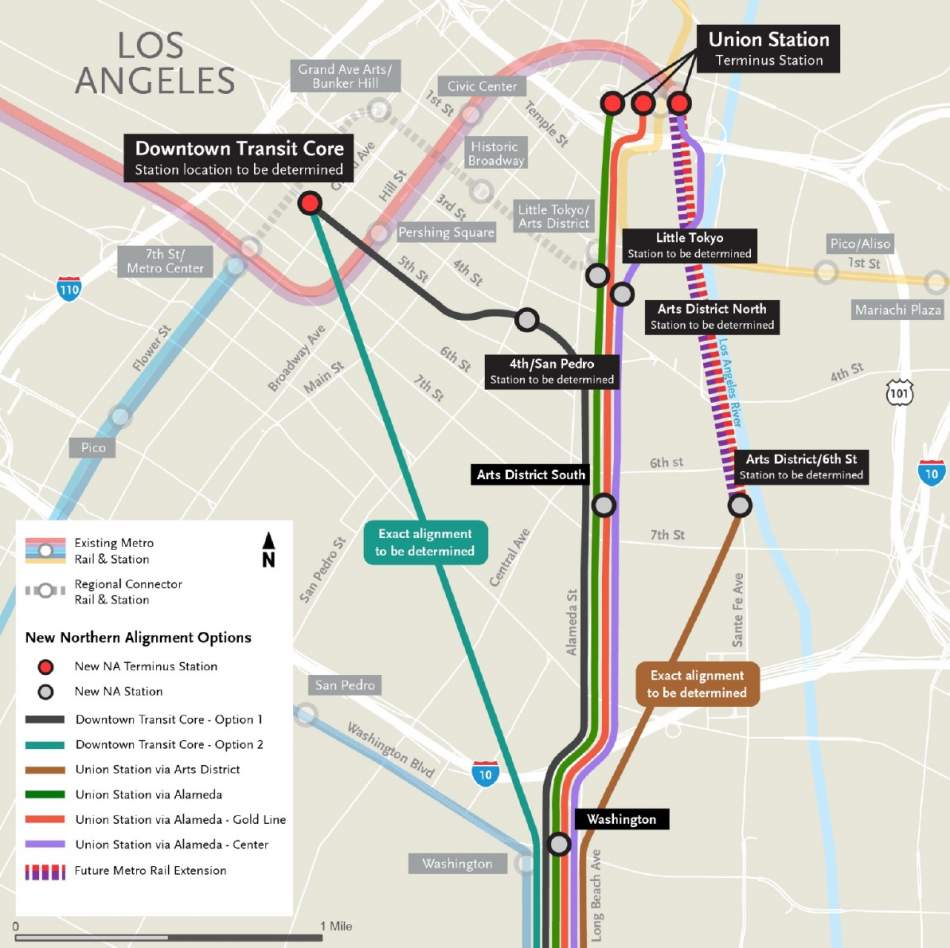

Originally, the West Santa Ana Branch was planned to connect Artesia with Union Station. The innermost alignment was undetermined, with options along both banks of the river as well as slightly inland to share right-of-way with the Blue Line, but the Downtown terminal was fixed. However, Metro has recently begun exploring new options. One alternative involves an outlying terminal in the Arts District, missing the subway connections unless Metro builds an unlikely one-stop extension of the Red and Purple Lines. Another involves an undetermined Downtown Transit Core location, near Pershing Square or 7th Street/Metro Center Station.

Union Station is clearly a more useful location than the Arts District: it's more central, and connects to the existing Metro Rail network. However, the plan requires tunneling for two miles through Downtown, and Metro is worried that $4 billion is not enough to account for the cost of putting the tracks underground. The only already-existing rail route from the south to Downtown is the Blue Line, and while it's technically feasible to have the West Santa Ana Branch share tracks with it, in practice, there is not enough capacity on the central segment to accommodate both lines as well as the Expo Line. One of the alternatives would have the West Santa Ana Branch share right-of-way with the Blue Line but not tracks; it would still need its own dedicated tunnel to enter Downtown.

The Arts District location is not a serious option. It is far from the busiest stations on the Los Angeles Metro Rail system, and it only connects to the Eastside, which is not a major ridership generator. In the future, the Regional Rail will connect it west to the Expo Line, but the busiest line in the system remains the Red and Purple Line, and thus a connection in that direction is imperative. This leaves two options: Union Station, and the Downtown Transit Core.

Without knowing the exact location of the Downtown Transit Core station, it is hard to precisely evaluate it as an alternative. The Metro Center station is the system's busiest, and in fact the busiest in the United States outside of New York, and this is before the Regional Connector opens and facilitates trips from the Eastside and Pasadena. Given the area's importance as a job center and a transit center, it would be useful to reroute the West Santa Ana Branch to have a transfer to this station. It would maximize network connectivity, on the principle that every pair of metro rail lines in a city should intersect, ideally in the center, and every pair of metro lines that intersect should have a transfer.

One alternative to the Metro Center option is to connect to the Red and Purple Lines and to the Regional Connector at two separate stations. This would avoid congestion at Metro Center, which could come from funneling all rail passengers through one transfer point. Subway networks in the former communist bloc often build three lines meeting in a city center triangle, and the Mexico City Metro's first three lines provide another example of this configuration. To build such a triangle, the West Santa Ana Branch would have to tunnel to connect with both Pershing Square and the future Second/Hope station on the Regional Connector.

Unfortunately, two limitations remain to any plan to treat the West Santa Ana Branch as a full metro line. First, it would connect Downtown with a low-density suburb, which means there is less justification for extensive tunneling to reach the best destinations. Second, it would be one-tailed, going just southeast. In comparison, the Regional Connector would provide for a two-tailed trunk line, going east-west (or north-south), which makes for better connectivity. Even the Red and Purple Lines connect to Union Station, a major draw because of rush hour commuter rail traffic to points west.

One resolution to the problem is to find a northbound rail alignment to connect to Artesia. But the only reasonable destinations to the north are Pasadena, which is already served by the Gold Line, and Glendale, which is already served by Metrolink.

However, there is a speculative modification that could permit the West Santa Ana Branch to continue north: severing the Blue Line from the Regional Connector. Right now, there are two light rail lines going south and west of Downtown planned to feed the Regional Connector: Blue and Expo. West Santa Ana would add a third. It might be better to construct a second central tunnel, but not exclusively for West Santa Ana, but for both West Santa Ana and the Blue Line. This tunnel would aim to end at Union Station and continue north to Pasadena and the Foothills. The under-construction Regional Connector would only serve the Expo Line and connect it to the Eastside. Alternatively, the West Santa Ana Branch could connect to the Blue Line and the Regional Connector, but then the Expo Line could get a dedicated east-west Downtown tunnel, about two miles long, connecting it directly to the Eastside.

The Expo Line's ridership today is 64,000 per weekday, and it is likely to keep growing. Moreover, increased development on the Westside is likely to add passenger traffic to the Expo Line. Thus, the ridership on the West Santa Ana Branch is unlikely to be higher than that of the Expo Line. The significance of this fact is that it is better from the perspective of capacity to give the Expo Line a dedicated city center tunnel rather than the West Santa Ana Branch. The Regional Connector is one tunnel, and light rail to Artesia requires a second tunnel, but it does not follow that the second tunnel must be dedicated to Artesia.

The upshot is that Metro should consider many more options than on its list of alternatives. A tunnel is needed, but could go in many directions, perhaps not even carrying the West Santa Ana Branch, if it is linked with the Blue Line and both use the Regional Connector.

The advantage of having so many options for tunnels is that if some options prove infeasible, it is likely that there will be another alternative that does work. Downtown is a constrained location with older infrastructure, and tunneling there is inherently more difficult than in an outlying neighborhood. This is why the Regional Rail is so expensive, with a cost per mile noticeably higher than that of the Purple Line Extension despite having smaller stations.

But with so many options, some north-south and some east-west, it is likely that Metro could find an alignment that is relatively simple to construct, while ensuring maximum network connectivity through having every pair of lines intersect. This more than anything would help keep costs down, permitting the project to go forward while sticking to its $4 billion budget. Metro is right to look at so many options, but it needs to look at even more, to be able to select the alignment that best meets the conflicting needs of high capacity, good network connectivity, and low construction cost.

- West Santa Ana Branch Archive (Urbanize LA)

Alon grew up in Tel Aviv and Singapore. He has blogged at Pedestrian Observations since 2011, covering public transit, urbanism, and development. Now based in Paris, he writes for a variety of publications, including New York YIMBY, Streetsblog, Voice of San Diego, Railway Gazette, the Bay City Beacon, the DC Policy Center, and Urbanize LA. You can find him on Twitter @alon_levy.