The California housing crisis is damaging our very existence. Homelessness is higher than any point during my lifetime. High housing costs are a drag on our local employers. Many working poor have a job, but live out of their vehicles. Many commute as many as four hours a day just to make a living. People are leaving our state to find the middle class American dream elsewhere. Most importantly, the outrageous cost of living may scare the young person that would move to California to create the next Disney, Bechtel, Google, Douglas Aircraft, or Intel from ever coming. Enough is enough.

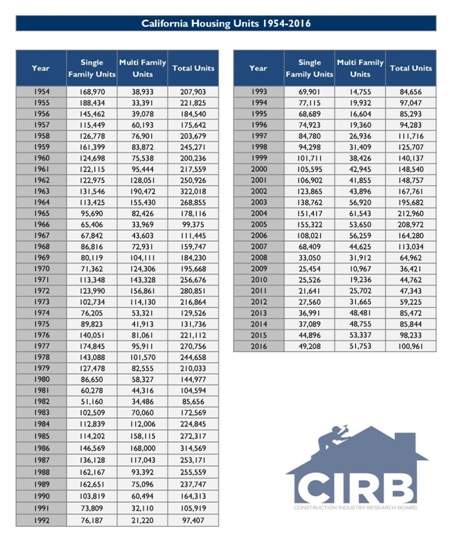

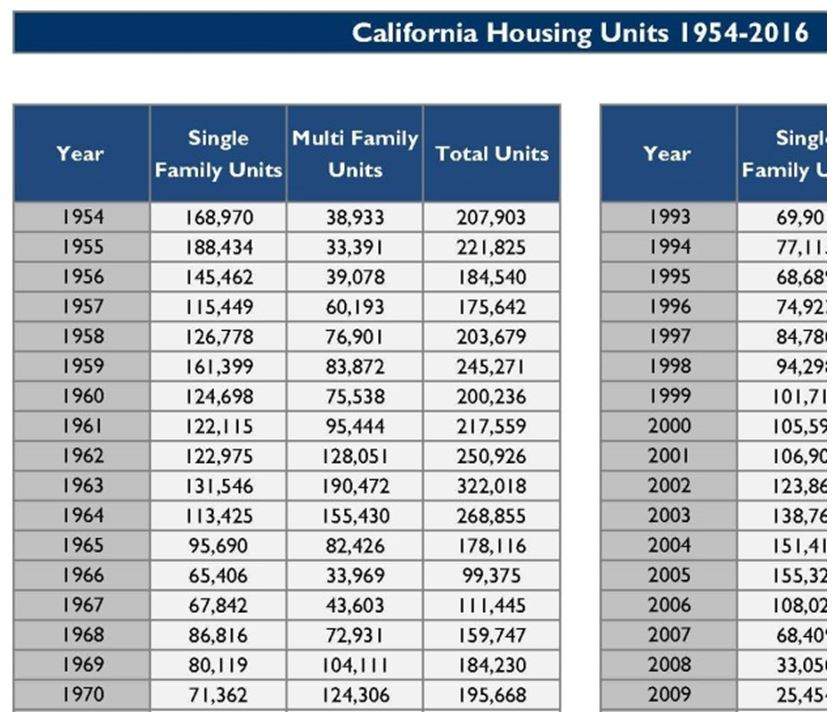

California state housing officials say we need 180,000 new housing units per year. A study by McKinsey, embraced by Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, says we need 3.5 million homes by 2025 (that’s 437,500 per year!). Today, despite out-of-control housing values and the strongest infill housing market in a generation, we are barely building 100,000 housing units per year.

I have been a new housing developer in California since 2005. It is more difficult today than it has ever been to bring new housing units to this state. California is the land of innovation; it doesn’t need to be this difficult. Taken from my day-to-day struggles to bring housing to our state, these are my 25 solutions to fix the California housing crisis.

1. Allow 100% Residential Development On Commercially Zoned Properties

The more I study California’s infill land inventory, the more I feel the easiest fix to our housing crisis is to allow more 100 percent residential housing projects on our underutilized commercial lots. People say California has run out of land, especially infill areas, to build more housing. We haven’t. There is plenty of available land on these commercially zoned lots.

The City of Los Angeles is the only jurisdiction in the state that I know that allows 100 percent residential developments to be placed on most of their commercially zoned lots. This is a big part of the reason they are a major state leader in housing production. Most other jurisdictions ban residential outright and some allow for residential to be placed above the ground level.

Banning housing on these lots is an easy way for cities that don’t want housing to not get housing. There is another reason for this: money. Housing generates revenue in the form of property taxes. Property taxes in California under Proposition 13 are essentially fixed from the time of sale. Proposition 13 incentivizes jurisdictions to not zone for housing because it doesn’t create much tax revenue. Commercial property creates property taxes and, most importantly, sales taxes. Allowing housing on these commercial lots is seen as a way to block sales tax revenue from ever coming in.

The problem is these properties are often not generating sales tax revenues for local governments. We have a retail apocalypse in this country. We had too many commercially zoned properties in California even before online shopping changed retail. Look at the commercial streets in your neighborhood. Vacant lots are abundant. Vacancies are everywhere. Most buildings on our commercial boulevards are grossly underutilized, often with no more than one story and no more than a .5:1 floor area ratio. Cities need to acknowledge that we have too much commercial land and that future sales tax generating commercial development will be impacted by online shopping.

We can’t trust local jurisdictions to make this change: many don’t want housing. Reforms have to come from the state. If there must be ground floor commercial, do it so it works in today’s economy. This is a mixed-use townhome project being currently being built in Los Angeles. The units on the street have commercial space at the ground level. The units off the street are pure residential. In pre-sales, the mixed-use units have been the best sellers. This is a prime example of how we can increase our jurisdictions' sales tax bases and add housing with scale.

In 2006, The City of Glendale adopted a specific plan for its downtown area. The plan allowed for the development of 100 percent residential uses on lots previously zoned for commercial uses on some of the city’s main commercial boulevards. As a result of this plan, Glendale has exceeded its state housing creation goals. Building on commercial land prevented the displacement of residents. Older stock rents in the city have risen slower than other parts of the region. Mom-and-pop businesses near the commercial blocks that were changed to allow 100 percent residential developments used to struggle. Now they are doing much better with plenty of new residents within walking distance to patronize. The plan created the increased the sales taxes jurisdictions love. This isn't hard.

2. Stop Killing Housing By Delaying Approvals – Honor Mayor Ed Lee’s Executive Directive

There is a saying, “Housing delayed is housing denied”. Many jurisdictions in California take three, four, or even five years to approve straightforward housing projects as a tactic to frustrate builders into giving up. By delaying projects this long, these jurisdictions are sending a clear message to future builders: “Do not come here”. Message received. In certain cities, California is filled with infill land appropriately zoned for housing at reasonable prices. The land is reasonably priced because there is no demand to acquire it and wait the five years it takes to secure approvals.

Nothing adds to the cost of housing more than the carry a builder pays waiting for approvals. There is nothing a jurisdiction can do to lower the cost of housing more effectively than approving housing projects in a reasonable amount of time. For years, over 80 percent of California has been off limits to me as a housing developer. I can’t afford to wait the three-to-five years it takes to start construction.

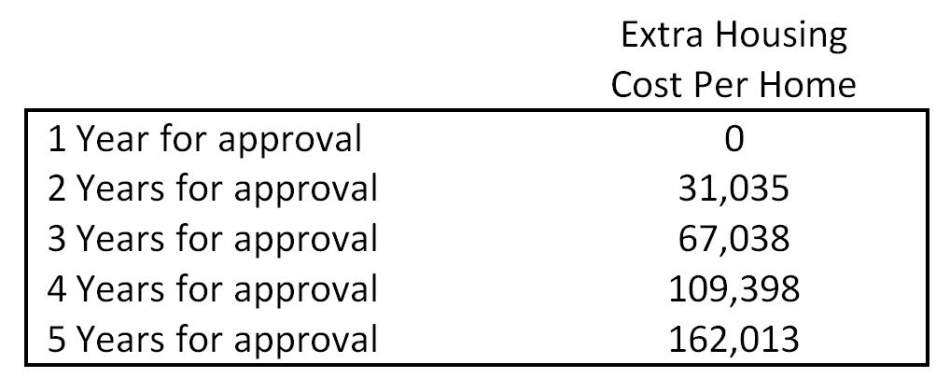

Let’s look at a basic case study to demonstrate how important this is. Let’s assume there is an acre of infill land currently zoned for 30 townhomes. These townhomes take 18 months to build. If the city approves the by-right project within one year, the builder can sell the townhomes and make 20% annual return on her money. The table below shows how much more the builder needs to charge his customers per home to make a 20 percent annual return if the city delays project approvals more than a year. Delaying approvals five years, as many California cities do today, can add over $162,000 to the price of a home!

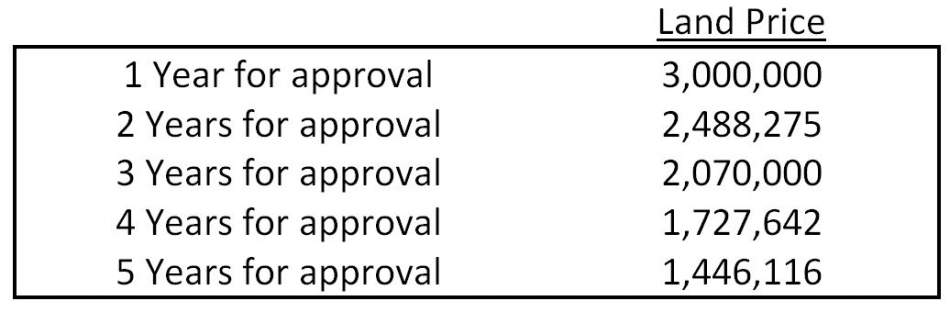

What happens in the likely scenario that a builder cannot pass the extra cost onto the homeowner? The builder will have to pay less for the land to make the same return on their investment. This is where “housing delayed is housing denied” comes into play. Look how much the builder’s purchasing power drops:

It is very possible the owner of this piece of property already has something built on the property that they are collecting rent on. Because it provides consistent cash flow, the lowest price she will accept is $3,000,000. By taking longer than a year to approve housing (even if it is zoned for it), the city has ensured housing never gets built. We can’t play these games in California anymore!

California does have a state law in place that is supposed to stop this from happening. It is called the Permit Streamlining Act. Unfortunately, the law has no teeth and can’t really be enforced (get used to hearing this).

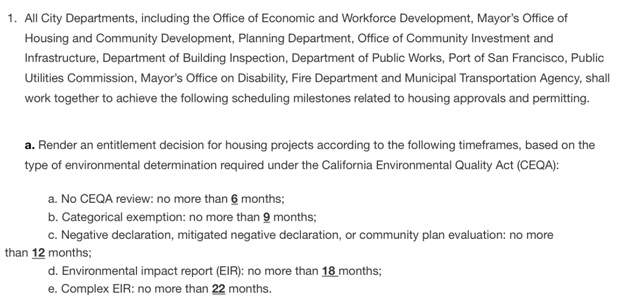

Last September, San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee issued Executive Directive 17-02. I believe this was the final Directive he issued before his death. The Directive outlines very reasonable timelines to render a decision on housing cases depending on their complexity. The City of Los Angeles’s Expedited Processing Unit has been meeting or beating these timelines for over a decade. There is no reason the rest of the state’s jurisdictions can’t meet these deadlines. If cities need to charge more to hire more planners to handle cases, do it. My tables show paying more fees for quicker approvals is very much worth it. We should honor Mayor Lee’s legacy by reforming the Permit Streamlining Act in a way that implements these below timelines for housing and penalizes jurisdictions that habitually fail to meet these goals (See rule #24).

3. Create New Zones For Missing Middle Housing

Often when we do change zoning in California, we do it for housing types that are very large and expensive to build. In November, I studied certificate of occupancies in the City of Los Angeles to date in 2017. I found that 47.3 percent of all new housing created came from projects sized fifty units or larger. On average it took over six years to create this housing. This timeline is way too long. We need housing today.

We need all kinds of housing in the state. There are numerous problems with having half of housing coming from “mega-projects” sized fifty units and over. They are the most expensive housing type to construct and they take longer to construct than smaller projects. This is why most new apartments you see are luxury units. Also, they often have to be financed with nontraditional, often foreign, financing sources. There is great risk relying on housing product with fickle financing to be a staple fix for our crisis. What happens if they go away?

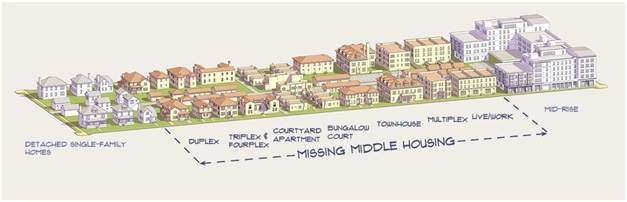

The one story single family home was the backbone of California’s post World War II housing revolution. We don’t have to go from one-story homes to all seven-story apartment buildings with two levels of underground parking. There is housing called “missing middle”.

Missing middle housing units are often two-to-three story duplexes, triplexes, and townhomes, compatible in scale with single-family homes that help meet the growing demand for a walkable urban lifestyle. They are much cheaper to construct than megaprojects. These savings are passed on to homeowners. They also take far less than six years to create. You can develop unentitled missing middle housing with an accommodating jurisdiction easily in under three years, soup to nuts. Missing middle needs to be a far more used new housing type to combat our crisis than it is today.

4. We Need Uniform Statewide Zoning Rules for Properties Within ½ Mile Of a Rail Stop

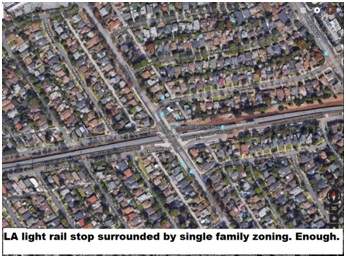

California taxpayers have spent good money over the years building out our rail systems. It is long overdue to capture that value. California can no longer afford to have single family homes within a ½ mile of our rails stops. Period. Upzoning single-family zones is the third rail of local politics. Local jurisdictions will not do it, so we need Sacramento to write a state law. There should be high density within ¼ mile of a rail stop. There can be a step down from ¼ to ½ mile but no 100 percent commercial and no single-family zoning.

If we do this, we can generally leave other single-family zoning in the state alone. If your house is already within ½ mile from a rail stop then you have already been impacted. All up zoning means is that you can cash out and move to a true single-family part of town. Last week, State Senator Scott Weiner introduced a bill, Senate Bill 827, to address this issue. Speaker Rendon and Majority Leader to be Atkins need to commit to moving it through committees. Governor Brown needs to use as much political capital to pass a bill like this as he did last year to pass cap and trade and the transportation funding bill.

5.We Must Woo The Publicly Traded Homebuilders Back To California

Notice from our historical building permit chart, we are currently building about as many multifamily units as 2005. But 2005 had triple the number of single-family units. The problem was that we were building these homes in far-flung suburbs, away from jobs, demand, and opportunity. Places like the Antelope Valley, Victorville, Bakersfield, Palm Springs, the Central Valley, and Northern California cities off the BART/Caltrain grid.

Many of these homes, especially the over 150,000 single-family homes permitted in 2005, were built by the “publics”. “Publics” are companies that trade on the stock market like KB Home, Lennar, Pulte, Beazer, and DR Horton. Publics are the most efficient homebuilders in the country. Because they trade on Wall Street, they have access to much cheaper equity and debt than privates. Because they have national purchasing power, they can construct housing for around 15-to-30 percent cheaper than a private. With the new tax bill, they also have a much lower tax rate than private home builders.

The publics are homebuilding machines. They can leverage their corporate offices to build housing cheaper than anyone. In order to get our building permit levels up, they must be a major part of the equation. It is interesting to note that because these companies trade on the stock market, they cannot buy unentitled land. The mousetrap to build these units was a private developer bought land unentitled, obtained the approvals, and then sold the property to a public to build the housing.

This was a very cost-effective, profitable process that brought housing to California for decades. The problem is today in California, the public home builder presence is a shell of what it was in 2005. The public’s bread and butter house is the detached single family home. Late in the last cycle some of the publics (KB, Lennar, Pulte) opened “Urban” divisions to build outside of sprawl. This is a condo building “KB Urban” built in Woodland Hills.

KB likely got their clock cleaned on this project when the Great Recession hit. So did all of the other public urban divisions. They quickly closed and never returned. Now in 2017, much of the building is in the urban infill areas, but the publics haven’t returned. They are building whatever missing middle is available, but nothing like before, and California misses their building efficiency. A few years ago Toll Brothers opened an urban division focusing on New York, New Jersey and the DC-Maryland-Virginia metropolitan area. Toll and the others need to return to California to help us with divisions like this.

These divisions will help the publics grow their stock prices with more exposure to California real estate. California will benefit from efficiently-built housing. We need a return to the model of private developers entitling a condo map, then selling to an urban division public to build. We will never get to 200,000 plus units a year without the publics returning. Returning to build in sprawl won’t help. They must return the urban divisions they started late in the last cycle.

Governor Brown needs to set up a working group with the leaders of the publicly traded homebuilders and determine what they need to reestablish urban divisions in the state. As Mayor, he had success wooing developers to come to Oakland. He can do it again.

6. Legally Enforce That All Jurisdictions Take Senate Bill 35 Seriously

In 2016, California passed package of fifteen bills aimed at addressing the housing crisis. The majority of the package won’t make an immediate impact on affordability, butte package had a jewel: Senate Bill 35 (SB 35). For jurisdictions that are not meeting their housing goals, SB 35 mandates streamlined approvals for housing projects that conform to existing zoning. To qualify for this streamlining, you must construct the project with prevailing wages (see rule #20) and include a portion of below market rate units. SB 35 is not perfect, but it has the potential to be the most important California housing bill of all time. This assumes everyone cooperates. SB 35 became law January 1, 2018. As of this writing I have initial concerns:

- In 2016, California passed a state bill allowing accessory dwelling units “ADU” to be built statewide. In the fall of 2016, in anticipation of the bill becoming law on January 1, 2017, California’s housing department (HCD) released this informational webpage. The site explained how the law would be implemented, and removed any lingering gray areas. HCD promised to post a FAQ on SB 35 before year end 2016. They missed that deadline.

- Before becoming law, dozens of local jurisdictions issued implementation memos outlining exactly how ADU applications would be processed. As of this writing on December 31, to my knowledge, only the City of San Francisco has issued an implementation memo on SB 35.

- There is widespread confusion on the technical details of SB 35. Ask six well-paid land use lawyers a specific question about it, you will get six different answers.

- I want to use the bill. I have called several jurisdictions asking them how I can begin my application process. Many didn’t even know the bill existed. None had any process in place.

- We have no official idea what jurisdictions qualify for streamlining under the bill. The development community is currently guessing on a piecemeal basis.

I am confident many of the interpretation questions in SB 35 will be cleared up shortly. I am not confident all (most?) local jurisdictions will follow the rules in the bill. How SB 35 is implemented in 2018 will be a big part of solving this crisis.

7. Give Our Local Communities Appropriate New Housing Goals And Mandate They Meet Them

Believe it or not, there has been a policy in place since 1969 that requires all California local governments to adequately plan to meet their housing needs. Every local government is given a number by the state of new housing units that they are expected to build over a period of time. These units are called the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA). There are two major problems with this process. First, the process is unenforceable and has no teeth, and thus many jurisdictions do not take it seriously. Second, the number of units given to most local governments as a goal is often far too low.

Under RHNA, local governments are supposed to zone their areas in a way that will accommodate meeting their new housing targets. They are supposed to take stock every few years through a document called the “Housing Element”. If they are not meeting their goals, they are supposed to adjust their policies in a way that will allow them to. This process is currently a joke. Cities that don’t want housing will take properties that are impossible to develop, and zone them for housing. “Ralph’s grocery store has a 40-year credit lease on these four acres of land?” “Great let’s zone it for 500 units and say we are doing our best to meet our housing goals.” Abuse is rampant. This is Liam Dillon’s magnificent deep dive into all of the shenanigans that take place during this process.

RHNA new housing goals should be the amount of new housing an area needs to build to bring housing costs under control. The current numbers do not reflect that goal. The Cities of Los Angeles and San Francisco do not qualify for market-rate streamlining under SB 35 because they have met their market rate housing targets under RHNA. If that is true, why do we have such massive housing affordability issues?

This entire process needs to be reformed by the California Legislature if we are to have any prayer of solving this crisis.

8. Measure Progress By Certificates of Occupancy Minus Units Demolished

Let’s take a look at 2017 new housing activity in the City of Los Angeles:

- In 2017, The City of Los Angeles has approved well over 20,000 new housing units.

- There have been 17,826 new housing building permits**

- There have been 8,638 new housing certificates of occupancy**

- There have been 2,501 housing units that have received issued demolition permits**

- The true number of 2017 housing units created in Los Angeles is 6,137 (8,638-2,501)

**Through December 25 per my Data LA counts,

For years, no major jurisdiction in the state has taken the housing crisis more seriously than the City of Los Angeles. Since taking office in 2013, Mayor Eric Garcetti has committed to investing in needed long-range planning and has made his development service departments run like a clock. If everyone acted like Los Angeles, we would have no crisis. That makes it all the more troubling that this city of over four million people could only bring to market 6,137 new housing units this year in such a strong economic environment.

It is important to count this way. As a way to prevent housing, rogue California jurisdictions often use design review to condition approvals in a way that the approved project ends up financially infeasible to construct. It is common for approvals to take so long, that by the time the project is approved the current construction cost environment makes development financially infeasible. Sometimes developers are financially incentivized by their investors to pull building permits, even if they cannot build. Even if construction does begin on a building permit, today most four-story and taller projects are taking two years or longer to construct. We need to know how much new housing is available now.

Someone new cannot live in an approved unit. They cannot live in a building permit. A new housing unit has not been created for them if one was demolished in its place. The only way we can track progress on the housing crisis is if we keep accurate score. To do this we need to keep track of how cities are meeting their RHNA goals by certificates of occupancy minus units demolished.

9. Allow Housing Construction To Begin Immediately After Planning Approvals

Often in California an “approved” housing project is nothing more than an “approval to get more approvals” before starting construction. It can often take well over a year, and sometimes two or three, to get these next approvals to finally start construction. We have discussed how project timeline is one of the most expensive parts of the cost of housing and one of the easiest ways jurisdictions can bring down costs. We need state laws that mandate best practices from some of the state’s best jurisdictions. Here are three:

- Projects that 100 percent conform to code should be allowed to process their building permit plan checks concurrently with planning approvals.

- Housing projects that are for sale (condos, townhomes, new single-family developments) need to go through a process of creating a “subdivision map”. In this process, a developer “cuts” a big piece of land into smaller pieces. The planning approval is only the tentative approval of a subdivision map. You still need to go through the final process of recording your subdivision map. This process can take well over a year. Jurisdictions have wildly different policies whether developers can start construction before a subdivision map is recorded. The best jurisdictions allow a builder start construction right after planning approval, assuming they sign a covenant that they will conform to their planning approvals. No more multiyear waiting after planning approvals to start construction.

- Building construction should be allowed before the issuance of any public works permits for work to be completed project’s construction. These permits for work often done in public streets can take over a year. There is no need to delay a project for this. They can be bonded for prior to construction start and plan-checked during the construction of the housing.

10. Be Very Careful Adding New Fees To Developments That Create New Housing

Construction is one of the last remaining manufacturing industries left in the United States that hasn’t significantly outsourced jobs out of the country. This is because no one has figured out how to do it yet. There is a reason most other manufacturing industries have outsourced: it is very hard to turn a profit manufacturing with American labor.

If housing creation in California was cheap and easy, we wouldn’t have a crisis. The two easiest ways jurisdictions can help to keep costs down are quick approvals (see rule #2) and avoiding unnecessary fees.

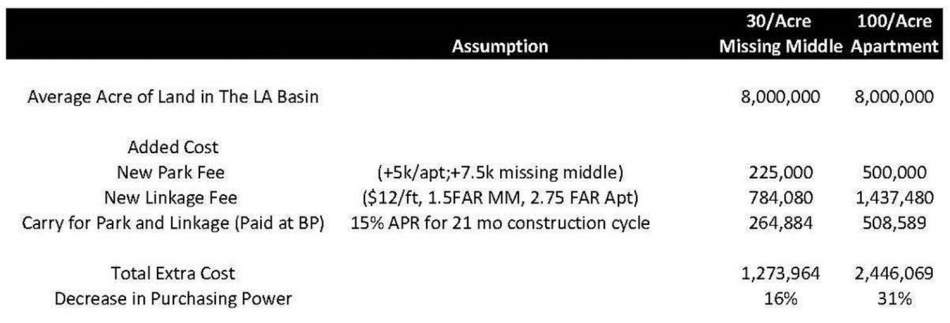

Two years ago the City of Los Angeles had some of the lowest fees for development in the state. For a project of 1,600-square-foot townhomes, the city’s various agencies charged about $33,000 per unit for the entire development process. Coming soon, thanks to two new fee ordinances, the city will have some of the highest fees in the state. That townhome will now cost over $60,000 per unit in fees.

Last year the city passed an ordinance increasing park fees. The fee for our hypothetical townhome went from about $3,500 per unit to $10,000 per unit (before carry). While Los Angeles needs more parks, I don’t understand why homebuilders in a housing crisis have to pay for them.

Last month, the city passed an Affordable Housing Linkage Fee Ordinance of on average $12 per square foot on new construction (Up from $0). This added $19,200 to the cost of our hypothetical townhome (before carry). You can receive an exemption from the linkage fee if you take advantage of the state’s density bonus laws to build mixed-income housing, but missing middle housing (like the townhome) is a less dense, more affordable typology that doesn’t have room to take advantage of density bonus laws.

Los Angeles doesn't have "land". It has property with an existing use, almost always cash flowing. To build housing, the land needs to be worth DOUBLE the market cap rate of the existing cash flow. Double because to sell, an owner usually needs to pay a broker fee and capital gains taxes. Because we have not built enough housing in California for decades, Los Angeles rents have skyrocketed. This makes existing uses (though often underutilized) much more valuable and harder to compel a sale for redevelopment land value.

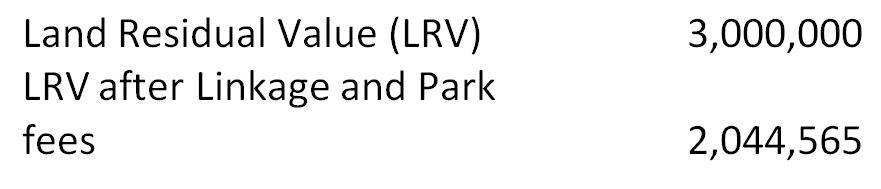

These two new fees have also lowered residual land values. These fees greatly decrease the chances of being able to compel a cash flowing land owner to sell. The below table shows how these fees decrease the residual land value purchasing power of a random Los Angeles acre by 15-to-30 percent.

To look at it another way, remember Rule #2? The acre of underutilized land, zoned for 30 townhomes, for sale for $3,000,000 and not a penny less? The new fees cut the value of that land by a third.

The owner of the property won’t take one penny less than $3,000,000. They will now either sell to someone who will keep the existing use, or keep the property. Thirty townhomes will not be built.

There is a state law called The Mitigation Fee Act that is supposed to stop these things from happening. Unfortunately, this law also has no teeth.

You can hire a consultant to write a study that says whatever you need it to say to justify additional fees. And adding fees like Los Angeles’ park and linkage fees make for great press conferences, sound bites, and newspaper articles. They make you look like you are doing something to fix our housing crisis. But adding to the cost of housing development, one of the last remaining manufacturing industries left in the United States, causes much less housing to get built. Please stop it.

11. Audit Planning Documents Regularly To See If They Are Creating Housing – Be Careful Not To Over Zone

Los Angeles’ Cornfield Arroyo Seco Specific Plan “CASP” has no parking minimums or unit maximums. Approvals are ministerial. The CASP is the best planning document I have ever read. It plans an industrial area next to downtown Los Angeles, adjacent to a light rail line. The plan maps out a transit-oriented, walkable neighborhood of the future. It is an urbanist’s dream. Passed over four years ago, it has not produced a single unit of new housing.

The foundation of the CASP is the recently opened Los Angeles State Historic Park. If you haven't been, go. It is magnificent. Considering all of the taxpayer money spent on the park and light rail, our housing crisis, and that this is well-zoned land centrally located with no need for evictions, no housing to date is a disaster. How is this possible?

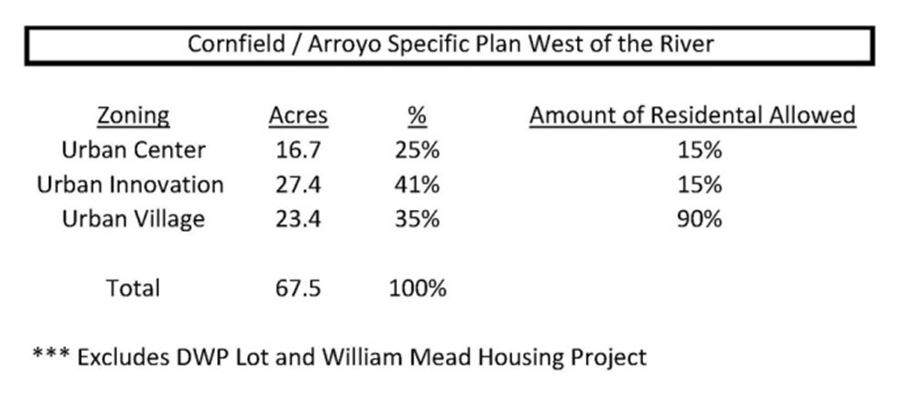

If you study the 67.5 acres of land in the specific plan west of the Los Angeles River, you’ll see that 65% of the land only allows 15% of a new project to have residential on it.

Los Angeles is unique for California in that it generally allows 100 percent residential developments in commercial zones (See rule #1). However, in the 2018 post-Amazon retail apocalypse, land that you can't put majority residential on has very little value. This is not the Planning Department’s fault. How could they have known when writing this between 2010 and 2013 that Amazon would crash retail real estate?

This leaves us with the 23.4 acres zoned Urban Village. The problem is that this provides max floor area ratio (FAR) of between 4.0 and 6.0. This is actually a problem. Zoning this land with that much FAR prices the land for that much FAR. It is very hard to build a building with more than 4.0 FAR with wood, which necessitates steel construction and higher costs. With land prices in the Urban Village priced for complex buildings, understandably no one has the guts to be the first to pay the high land price and build an expensive building in an industrial wasteland.

Complicating the problem more is, as of November 2017, just five entities control 37 percent of these 67 acres. Eleven entities control 58 percent of the land. The entities that control this land are generally very liquid and well capitalized. With our housing crisis, they own scarce, valuable assets. They are in no hurry to sell.

After four years and no housing, it is clear the CASP needs to be adjusted as soon as possible. The first adjustment is, post-Amazon, they need to allow majority housing in the Urban Center and Urban Innovation zones (See rule #1). Next, I would drop (you heard me, drop), the max FARs in the Urban Village zone starting at a fixed date in the near future. This would compel the current owners to make a decision to build or sell to someone that will.

The CASP is a classic case study that even the best written, most well-intentioned planning documents can go unused. The CASP can happen anywhere in California. With our current housing crisis, it is important to constantly evaluate the effectiveness of how plans are creating housing.

12. Incentivize and Remove Planning Approvals For As Much Affordable Housing As Possible

Government subsidized affordable housing is some of the most difficult housing in California to develop. You need to compete with market-rate developers to acquire land. You need to secure approvals, often in the face of stiff neighborhood opposition. When approved, you need to secure public funds to build the project. We have never had enough public funding for affordable housing. The recently passed tax reform bill in Washington will make access to these funds even scarcer.

With all of these obstacles, builders of affordable housing should receive priority treatment streamlining their approvals. Senate Bill 35 is a great start. Affordable housing in virtually every California jurisdiction qualifies for streamlining under SB 35.

In Southern California, the City of Los Angeles has proposed a Permanent Supportive Housing Ordinance. This proposed ordinance speeds approval times and, most importantly, provides many common sense housing incentives not available to market rate developers. The city should pass this ordinance and the California Legislature should look at it as a statewide model.

13. Reform, don’t repeal The Costa Hawkins Act and The Ellis Act

The Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act is a state law that bans rent control on all single-family homes, all condos, and multi-family units built after 1995. The Ellis Act is a state law that allows apartment landlords to evict tenants in order to “go out of business”. Often this means to demolish an apartment building to build a new residential building. There is intense pressure from affordable housing advocates to repeal both laws this year.

Many quality academic works show that rent control benefits a chosen few and raises the rents for everyone else. I agree with those works. But guess what? I don’t care. I live in the real world. With real people, that have real problems. There is a human face to this crisis. An academic work cannot help the 92-year-old widow on a fixed income with no family and no place to go. It is not her fault our state neglected to build enough housing for decades. Both of these bills need common sense reforms.

The Costa-Hawkins Act will never be repealed. The apartment lobby is too strong. If it were to be repealed, new apartment buildings would not be built in California. Multi-family residential development is some of the most expensive construction there is. This Reddit thread explains why most new multi-family construction is luxury development. Long story short, it has to be to justify building at all.

Often when a building is complete, due to high land costs, skyrocketing construction costs, and long development cycles the building does not earn a market appropriate rate of return. The building needs a few years to “season”. To do that, it needs to charge market rents. If you take away the ability to charge market rents, the groups that finance California apartment development will place their money in alterative assets.

There is room to reform Costa-Hawkins. Maybe rent control doesn’t start for 15, 20 or 25 years. Maybe older single-family homes should be rent controlled. Maybe annual rent increases at first can be more than the rate of inflation, but not unlimited. I would like to see an academic, not an activist, propose some solutions. We have the brain power at the University of California to come up with practical reforms.

In the wake of the Great Recession, “Ellis Acting” tenants to redevelop underutilized lots was generally an inconvenience, not a life changer, for tenants. Rents were cheaper, and tenants could generally relocate within the neighborhood. In 2018, that is often no longer the case. If you Ellis Act on a property, you are almost certainly turning the lives of multiple tenants - often living on the margins - completely upside down.

Once again, the Ellis Act is also not going to be repealed. The apartment lobby is too strong. So we can either ignore this problem and continue the misery, or we can look at common sense reforms. We also have far too many underutilized infill properties, often zoned for more than 10 times the existing use, to completely ban demolishing buildings with tenants. We need reforms that will protect and treat with dignity our tenants that are low-income, elderly, disabled, or have children. The current relocation fees often do not come close to doing that. I propose the following reforms:

- Jurisdictions must give priority placement in affordable housing lotteries to any tenants that are low-income, elderly, disabled, or have children who are evicted under the Ellis Act. The relocation period needs to be extended from 12 months to 18 months. This will give jurisdictions time to place the tenants.

- Make the relocation fees as high as legally possible. This will incentivize developers to only use the Ellis Act on the most underutilized of properties.

- Any family with children in a particular public school gets to stay in that public school if they are relocated due to the Ellis Act. There are several situations where families stay in apartments only because of a certain school district. Allowing them flexibility in relocation while keeping their children in their preferred school will help many situations.

14. Publicly Funding Construction Of Below Market Rate Housing Is Important, But Should Not Be Our Primary Focus

Repeat after me: The California taxpayer cannot afford to construct housing for every household in the state that earns lower than the median income. Unfortunately, there is also no way market forces can house those living on the extreme margins. We must continue to actively look at funding sources to provide this type of housing. However, the great majority of our state’s new housing must be built privately, helped by the solutions outlined in this article.

Whenever someone runs for office, often the first, and sometimes only, concepts they discuss for housing solutions are raising public funds for below market rate housing, and the repeal of both the Costa Hawkins and Ellis Acts. Other effective solutions need to become part of our narrative. Market forces efficiently scaling the production of housing can provide the majority of our new housing supply and take the burden off taxpayers. We did it in California after World War II, and we can do it again.

15. Make The Los Angeles Small Lot Subdivision Ordinance Statewide Law

Taken from the Los Angeles Department of City Planning website:

“Adopted in 2005, the Small Lot Ordinance (“Ordinance”) established a new hybrid housing typology that looked and functioned like row townhomes but where each unit was built independently on individual “small lots”. It combined the benefits of a single-family home and its full fee-simple ownership of building with the conveniences of a townhouse lifestyle. The Small Lot Ordinance was intended as an innovative housing tool to encourage the development of alternative fee-simple homeownership in areas zoned for multi-family and commercial uses.”

This is a Small Lot Subdivision “SLS” unit. You take a multifamily or commercial zoned piece of property and cut it into little pieces. Everyone owns their own approximately 1,500 square feet of land and a single family home that often looks like a modern San Francisco style row home. No common walls or foundations. Often there are just six inches of air between homes.

SLSs are usually the most affordable single-family home available in each Los Angeles neighborhood. You trade lot size for more affordability. Often the customer is a first-time homebuyer looking to establish equity and own their own small piece of Los Angeles. This is the modern-day equivalent of our prior generation that bought new ranch homes in L.A. Banks and private equity investors love placing money in SLS projects as they don’t require condo construction insurance. It is also simpler construction than a large podium project, so you can produce homes cheaper and faster.

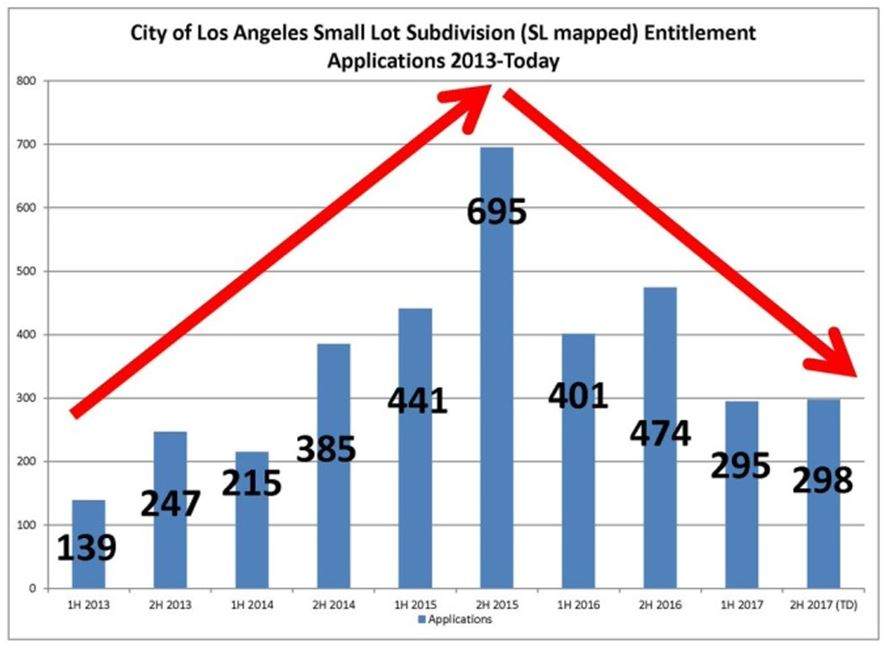

And yet SLSs are dying in Los Angeles. Los Angeles has run out of missing middle zoning, and they are not creating any more of it in plan updates. The city has recently looked to tighten rules on the development of SLSs. Recent increases in fees (See rule #10) has hit SLSs hard. Entitlement applications for SLS have dropped. As I explain here, I worry the typology is dead in Los Angeles.

In order to build this type of home, you need an ordinance and an appropriate amount of underutilized missing middle zoning (see rule #3). San Diego passed a SLS ordinance a few years ago; it has been a flop. This is because they passed an ordinance, but there is no properly zoned land in the City to make use of it.

SLSs are California’s homes of the future. They provide ownership, not rental opportunities to our younger generation. We should be building tens of thousands of these homes up and down the state every year. I am calling for the California Legislature to pass a statewide Small Lot Subdivision bill in the spirit of the statewide Accessory Dwelling Unit “ADU” bill they passed in 2016. I suggest the state uses a similar approach with small lot subdivisions as they did with ADUs

- Write a base ordinance that will serve as the law for every jurisdiction unless a local jurisdiction adopts a local ordinance.

- As of December 30, 2017 (One year after passage), only 104 of the state’s 540 jurisdictions (19.2%) have adopted local ADU ordinances

- Establish minimum requirements that every new local ordinance must meet.

16. CalPERS Needs To Start Investing In California Homebuilding Again

CalPERs is an agency that manages the pension and health benefits for over 1.6 million California public employees, retirees, and their families. CalPERs is the largest pension fund in the United States.

CalPERs started investing in California homebuilding in 1992. They invested in the construction of all types of California housing: single family housing, multifamily housing, senior housing, urban infill housing, all types of housing. For twenty years, CalPERs was the player in financing new home construction in the state. In this transaction alone they financed the development of 22,000 housing units. During the Great Recession, CalPERs took huge losses on its residential housing portfolio. By 2012, they had basically exited the space and have never returned. They are greatly missed. The funding hole they left has not been filled.

CalPERs made the same mistake we all made before the Great Recession. We were building a lot of housing, but we were building them in the wrong parts of the state. Places that were wrong from an environmental, economic, urban planning, and practical standpoint. CalPERs was heavily invested in these areas. They were underinvested in the urban infill areas that quickly recovered.

In order to meet our housing goals, CalPERs must reenter the residential construction financing market. In order to avoid the mistakes of the past, they should focus investment on urban infill and transit-oriented development. I have heard nothing from any of the candidates for Governor or Treasurer about CalPERs reentering the residential construction business. This needs to be a campaign issue.

17. We Need To Look At Dodd-Frank Reform

Today, it is so difficult for a homebuilder to get a reasonable construction loan to build California housing. In the lead up to the financial crisis, nearly any developer in California could get a low-interest, high-debt non-personally guaranteed construction loan regardless of important things like the project’s location, and the experience and wealth of the developer. All sorts of construction loans for housing that never should have been issued in California were issued. When the Great Recession hit, these banks took heavy losses on these construction loans. Many banks that we thought were “too big to fail” did just that.

In response, Dodd-Frank (Nationally) and Basel III (Globally) were 2010 policies aimed at addressing the financial crisis. For the past eight years, they have done exactly that, but the policies have been bad for housing creation. These policies contain language that makes it much more difficult for banks to issue risky loans like construction loans. To issue these construction loans, banks would now have to keep larger cash reserves. This makes construction loans less profitable and more unattractive for banks to issue.

While the reforms were needed, they have gone too far in construction lending. Today, I pay a bank about 2.5 times in interest and fees what I paid 10 years ago. This is very common for private home builders like me. Financing for a private homebuilder to build projects sized 6-to-50 units (once our state’s bread and butter) remains very hard to secure, and much more expensive than before. Those extra costs are either passed on to the customer or make many projects infeasible to develop.

In order to get more housing in California, the federal government must look at common sense reforms to the Dodd-Frank Act that allows for more homebuilding without turning our financial system into a casino again.

18.Fannie Mae Needs To Finance Construction Loans For Homebuilding

Fannie Mae, a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE), describes their business as “our financing makes sustainable homeownership and workforce rental housing a reality for millions of Americans”. Fannie Mae provides financing that allows the acquisition of several kinds of real estate. As a staple, Fannie Mae purchases the mortgages of the homes of many Americans. This is good.

Fannie Mae also provides financing for other things not so good. If you want to buy a non-rent controlled apartment building and raise the rents on all of the tenants, Fannie Mae will give you a low-interest mortgage to do just that. If you want to go into a working class, gentrifying neighborhood and buy up to 10 homes that take away homeownership and potential upward mobility from up to 10 neighborhood families, Fannie Mae will give you the mortgages. If you want to do what private equity giant Blackstone did: buy foreclosures during the Great Recession, evict homeowners, and then rent back to them at higher prices than their old mortgages, Fannie Mae will back the debt. What Fannie Mae will not do, is give you a construction loan to build California housing developments.

Part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, Fannie Mae was established through adjustments to the National Housing Act to make housing and home mortgages more affordable. During the Great Depression, with so many unemployed blue collar Americans (sound familiar?), FDR saw homebuilding as a key part of providing employment and stimulating the economy. Look how many homes were built in California in the 1950s and 1960s! We had a homebuilding revolution; today we need a new one. It is time for Fannie Mae and the other GSEs to remember their original missions. They need to start programs that provide construction loans to build California housing.

19. Digitize and Open Source Zoning Information For All Property In California

Our housing crisis is, in part, a crisis of a lack of widely available information. Developers lack efficiently presented information about opportunities to create housing in the state. I count 540 jurisdictions in California (58 counties, 482 incorporated municipalities) that can approve housing. Each jurisdiction has its own unique zoning code with specific plans, zoning maps, overlays, and various timetables to approval. It is absolutely impossible for any one person to be knowledgeable about all of these jurisdictions, much less the expert level needed to responsibly place millions of dollars of capital into a development project.

When looking at a potential housing development in California, it could take over an hour of research on the internet just to figure out what the allowable use type and density are for a property. This is a grossly inefficient use of time in 2018. I, like many California developers, have access to sufficient amounts of capital begging to be put to work to build housing in the state. I know for a fact that many opportunities exist in these 540 jurisdictions that none of us are aware of.

Real estate developers and brokers are generally not research-oriented people by nature. For decades, the model for housing development has been to not focus too much on zoning but rather to get approvals through lobbying and relationships with local councils. This process is not a sustainable way to deliver the amount of housing California needs to meet our housing goals. It is time to bring modern technology into the industry to price land more efficiently and increase housing opportunity exposure to available capital.

We need to make the California land markets more efficient. If we know the land use, max density, and timeline to approval, developers can price land in a matter of minutes. The problem is it takes too long to find these simple facts out one-by-one. I am confident there are a myriad available housing opportunities in California with great zoning where buyers and sellers can agree on a value. However, to know about the opportunity you need to read page 69 of a 169-page specific plan document.

Trust me from experience, many California landowners have no idea what the possible land use is for their underutilized properties. Often they are shocked to know the value and happy to sell. We need to help make this happen more often. The City of Los Angeles has a wonderful system zimas.lacity.org. You can punch in the address or assessor's parcel number of any property in the city and figure out what you can build in a minute or two. This is a statewide model. It won’t happen statewide so I have easier reforms.

- Every jurisdiction at a minimum must put their zoning map and a downloadable spreadsheet containing the address, assessor’s parcel number, lot size, zoning, and max density of every property in the city on the front page of their planning department website.

- Every jurisdiction must put a six-page max matrix summarizing zoning regulations. No more one-hour deep dives on the internet to figure out basic things like density. The statewide model should be this summary L.A. City puts out.

- Every jurisdiction must put a simple one-page document describing the approval process for all kinds of housing with an estimated timeline for approval.

- Whenever a jurisdiction updates a community plan, adds a specific plan, or does any general plan or zoning changes, they must update this data and contact The California Housing Department (HCD). HCD will then post on their website to inform the development community.

This is vital. Once we have the raw data for all of the underutilized land available for housing in the state, Silicon Valley can take over. They can link this data to ownership data on title to create apps to target what sites can produce housing and who to contact. Most importantly we can write algorithms to quickly identify where the best places to build housing are, value the land promptly and immediately being negotiations with these landowners. Give us the raw data, and Silicon Valley can take it from there.

This will make the California land market dramatically more efficient and increase housing applications. In my experience the majority of land transactions happen off-market. A developer reaches out to an owner. This will speed up that process. There is abundant capital sitting on the sidelines currently begging to be placed into California housing opportunities. Open sourcing our property data will help to expedite efficiently placing that capital to solve our affordability problems.

20. The Building Trades Need To Educate Builders on Prevailing Wage Requirements

Every housing bill passed in Sacramento last year that incentivizes housing production, including SB 35, requires paying prevailing wages to the construction workers that build the projects. In November 2016, Los Angeles voters passed Measure JJJ, which mandated housing projects approved with a zone change pay prevailing wages. Prevailing wage is now the law of the land for many paths to building housing in California. There is one major problem, most of us builders have no idea how to get started as prevailing wage builders.

For decades, market-rate housing in California has been built without prevailing wage. The market rate building community, while they love to complain prevailing makes building impossible, has no idea exactly how much prevailing adds to construction or how to do the required reporting that goes along with it. I believe in the general idea of prevailing wage; workers should be able to afford to live in the homes they are building. Depending on how much more it costs, I am happy to trade benefits like zone changes and streamlining for paying prevailing wage. I’d rather give the money to the California worker than to a bank as interest carry. But until we figure out the details, we can’t know if these new programs are viable.

Zone change applications in Los Angeles, especially for wood-framed construction, have fallen off a cliff since the passage of Measure JJJ. I believe it is because many established builders are not curious enough to learn new tricks. I have been on a nine-month journey to figure out prevailing wage. I am stick stuck and so are my peers. The organizations that are putting prevailing wage in housing bills need to do a much better job educating the market rate community how to build like this. They can accomplish their goals of increasing hours for their workers if they simply educate us market rate builders with presentations and seminars. There is a younger generation of developers open to a strategic partnership with labor to fix our housing crisis.

21. Give Our 120 California Legislators a Pay Raise

California has 58 counties and 482 incorporated municipalities. Even if they wanted to (many don’t) this many jurisdictions are too fragmented to solve our housing crisis. Solutions must come from the State Legislature. Sacramento must pass housing laws that give local Councilmembers the political cover to say, “I’d love to disapprove this housing project, but I can’t have our city break state law”. To pass these laws we need legislators that care about housing and are laser-focused on passing laws that solve the problem.

In the current Legislature I count three members with this focus. We need at least two dozen to get the proper momentum. In 2017, four Assembly seats have had mid-session resignations in Los Angeles alone. Every time an opening has come up, I reached out to an extremely qualified peer living in the district to run for the seat. People that would be committed to writing, and passing housing laws. The answer is always the same, “I can’t afford the pay cut.” A seat in the California Legislature is not dog catcher. It is law making for the world’s fifth largest economy. We deserve to have the most qualified people possible serving in these seats. A Los Angeles City Councilmember makes about 1.8 times more than a legislator in Sacramento. In 2018, the salary for the Los Angeles City Planning Director will be more than double that of the Speaker of the California Assembly. It is long overdue that we close that gap.

22. Care About State Elections

You may not know who your State Senator and Assembly member are, but they are a very important part of fixing this. They need to care about housing solutions for anything to happen. Unfortunately, I feel most California Legislature elections fly under the radar. I often feel the powers that be “anoint someone” to these seats.

This needs to change. The endorsements the editorial boards of our state’s newspapers give matter greatly in determining winners. Every week, I read countless wonderful articles in these papers about the housing crisis. I am calling on our papers of record, especially The Los Angeles Times, The San Diego Union-Tribune, The San Francisco Chronicle and The Sacramento Bee to press candidates hard on these issues. Their answers to housing policy should be a material part of determining who to endorse. It is time we start sending people in bulk to Sacramento that get these issues.

23. We Need More Labor

Even if we had the political will to build over 180,000 housing units per year in California, we couldn’t. We do not have the labor force in place to build that many homes. We barely have enough to build the half of that we are currently building. I treat our subcontractors like gold. I know they can leave for a different job at any time. Every day on job sites in California recruiters poach framers, pipefitters, and drywallers right off jobs. They give them a raise on the spot to leave to a new job. This is part of the increase in housing cost. It costs us today just about double what it cost 10 years ago to construct a house. It is not just construction. In agriculture, we are letting our state’s crops die because there is no one to harvest them.

We cannot solve our housing crisis without addressing this shortage. I have three solutions.

First, we should actively recruit out-of-state skilled workers that have lost manufacturing jobs.

Second, our State’s Community Colleges need to invest more in programs to produce the next generator of entrepreneurs in trades like carpentry, electrical, plumbing, HVAC, concrete, and utility work.

Finally, we have to overhaul our nation’s immigration laws. The Dream Act is not good enough. We need comprehensive immigration reform that brings the nation’s undocumented out of the shadows and welcomes them with dignity to the workforce. The bipartisan crafted, “Gang of Eight” bill, would be a good place to start.

24. Threaten to Take Away Local Control From Bad Actors

No matter what reforms we pass, it is possible (probable?) that some jurisdictions simply will not follow laws to allow housing construction. One of the few ways to ultimately compel them is the threat to take away their local control. In California we have organizations called Council of Governments (I count 20 in the state) that are in charge of regional planning issues. We need to pass a bill that land use policy and project approval transfers to the Regional Council of Government when a jurisdiction repeatedly fails to follow state housing laws. Think of it as the “housing death penalty”. This threat will give local councilmembers the sound bite “I’d love to not zone for housing, but we can’t lose our local control” to make sure they do the right thing.

25. We Need a Real Lobby

Gun rights advocates have the National Rifle Association and Wayne LaPierre. Reproductive health advocates have Planned Parenthood and Cecile Richards. To be successful, the California housing movement needs a similar organization and a leader to rally behind.

There is a movement out there, the “Yes In My Backyard (YIMBY)” movement. It is time to legitimatize and rally around them as the leaders of our cause. Brian Hanlon of California Yimby and Laura Foote Clark of YIMBY Action are CA housing advocates. Unlike other lobbies, they do not develop housing. They advocate for housing. All different types of housing. They have a podcast. Political candidates have come from this movement like Sonja Trauss for San Francisco Supervisor. I did not take either Brian or Laura seriously at first. Today I’m confident the 2017 housing package would not have passed without their efforts. Brian Hanlon has moved to Sacramento and created California Yimby to advocate for housing reform. He is our leader.

To be successful, California Yimby needs all of our support. Become a member. Donate. Volunteer. All of the fragmented YIMBY movements statewide need to organize together under the tent of California Yimby. Future candidates should covet a CA YIMBY endorsement the same way they currently do for one from Planned Parenthood. With the proper support, Brian has the motivation, knowledge, and skills to influence housing policy more than any non-elected since Howard Jarvis. Yes, the Howard Jarvis of Proposition 13 infamy. We are in the first inning of a revolution that rekindles the spirit of California’s post-World War II housing production boom. It is time for everyone to get on board

People care about our housing crisis. We discuss it constantly, and now is time to do something about it. These solutions are going to require a group effort. We need the California Legislature, local jurisdictions, local planners, publicly traded homebuilding companies, affordable housing advocates, the private development community, CALPERs, Fannie Mae, the State Building Trades, lobbyists, our newspapers of record, YIMBYs, and most importantly the California voter to come together to fix this. We have tackled much more difficult issues in this State. We can do this.

@housingforla is a Los Angeles based residential developer. For inquiries, email housingforla@gmail.com