At the beginning of this month, Senator Scott Wiener (D – San Francisco) introduced a bill in the California state legislature, SB 827, with the aim of facilitating extensive transit-oriented development (TOD) statewide. The bill would preempt local zoning regulations near public transit routes, permitting the construction of mid-rise housing within a half-mile of rail and bus lines. This has the potential to overturn decades of suburban planning, creating not only new housing in Los Angeles but also new demand for under-construction public transit projects funded by Measures R and M.

The bill comes with the support of the YIMBY movement, or Yes In My Backyard, a national movement aiming at liberalizing zoning laws in order to produce more urban housing, reducing housing prices. YIMBY has had particular success taking root in the politics of San Francisco, where the strong economy has raised apartment rents to stratospheric levels. Alongside Wiener, two more members of the state legislature are co-sponsoring the bill, both from the Bay Area: Assemblymember Phil Ting (D – San Francisco) and Senator Nancy Skinner (D – Oakland).

The text of the bill is currently in flux; Wiener said he is taking amendments, and the final version may look dramatically different from the current one. But right now, the rules are as follows: within a quarter-mile of a bus route running at least every 15 minutes at rush hour, or within a block of a train station or the intersection of two bus routes, it would be legal to build residential developments up to 85 feet in height, with as little parking as the developer wants; within a half-mile of a train station or the intersection of two bus routes, the same rules apply for buildings up to 55 feet in height. The bill would not force developers to build this high: it only says that they have the right to do so, regardless of local zoning.

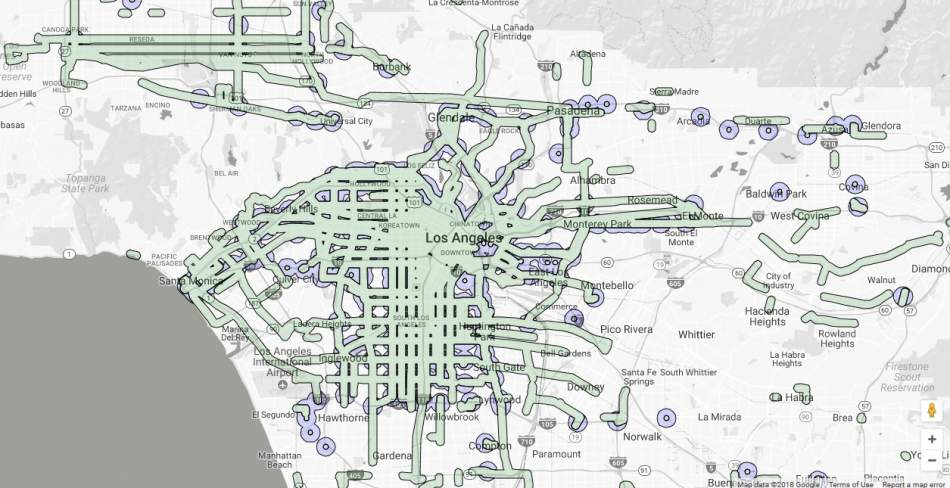

In Los Angeles, the bill would overturn low-density zoning in large swaths of the city. Nearly every major boulevard in Los Angeles – as well as those in many adjoining jurisdictions – has a bus running at least every 15 minutes at peak hours, and even farther out, train stations provide a large zone in which developers could build apartment buildings.

YIMBY activist Sasha Aickin made an interactive map of which parts of the state would be affected if the bill passed. In most of the area between Glendale, Lynwood, and Santa Monica, 85-foot-tall buildings would be permitted, as the arterials hosting buses are spaced a half-mile apart.

Stephen Smith, who runs the popular Twitter account Market Urbanism, believes SB 827 could be a game changer for both public transit and housing. According to Smith, the most demand for housing is in rich urban neighborhoods, especially the Westside. With areas that are currently single-family opened to mid-rise development, middle-class domestic migrants coming in to work high-skill jobs would find new housing in the most desirable areas. In contrast, development pressure in working-class neighborhoods currently undergoing gentrification would decrease.

USC Professor Lisa Schweitzer, who teaches public transportation policy and has clashed with YIMBY leaders in the past, agrees. She views upzoning wealthy areas as holding the promise to relieve gentrification pressure on low-density areas. But she also views it as “a good opening salvo,” which could be modified in the future to incorporate affordable housing mandates.

While the goal of the YIMBY movement is to build more urban housing, SB 827's focus on TOD holds special promise to help fill the region's flagging public transit system. Here, the fact that the bill is likely to have the most impact on the Westside is the main feature.

The busiest bus corridor in Los Angeles is Wilshire. Measures R and M include money for the Purple Line extension, running mostly under Wilshire from the line's current terminus in Koreatown to the VA Hospital in Westwood. This under-construction subway is projected to see 81,000 riders per weekday, the most of any rail extension in the area.

But the Purple Line extension's high ridership comes at a steep cost. Despite the nearly-unanimous support for the project from good transit advocates, it is in fact extremely expensive for the estimated ridership: with recent cost overruns, its budget is $7.2 billion, or about $90,000 per rider. The extension's viability depends on whether it can induce TOD, and SB 827 may be the only way to ensure that it will.

The Westside has had severe problems with NIMBYism. Beverly Hills launched an unsuccessful fight against the Purple Line extension since it is planned to tunnel under Beverly Hills High School to reach Century City. More recently, the Beverly Hills City Council declared its intent to fight SB 827. Two members of the West Hollywood City Council have also opposed SB 827 on the grounds that it would cover nearly their entire city; their demands include affordable housing mandates, but they also insist that SB 827 not apply to areas zoned for single-family housing. Within Los Angeles proper, City Council member Paul Koretz, representing the Westside, also came out against the bill, telling the Los Angeles Times that “I would have a neighborhood with little 1920s, ‘30s, and ‘40s single-family homes look like Dubai 10 years later.”

The YIMBYs would counter that what the elected representatives of the Westside view as a bug, the YIMBY movement views as a feature. With rules limiting the Westside's ability to restrict high-density housing, TOD could come to the area, helping fill subway trains that are likely to run well below capacity.

A typical subway line with run-of-the-mill signaling can run approximately one train every 2.5 minutes at rush hour, and with more modern signaling, it is possible to run a train every two minutes or even less, down to about 90 seconds. The combined Red and Purple Line trunk runs every five minutes at peak frequency, and ridership at the two dedicated Purple Line stations is weak. TOD on the Westside and in Hollywood would help fill this line, allowing it to reach the ridership level typical of busy subway lines in world cities like New York and London.

Accommodating additional population growth in Los Angeles would not just have an impact on the Wilshire corridor and the Red Line. Much of Long Beach and Pasadena would see additional growth, as would the parts of the Westside near the Expo Line. Potentially there may even be growth on the Blue Line in South Los Angeles, the Eastside Gold Line, and the under-construction Crenshaw Line, but as those run through poorer areas, and are unlikely to see much new demand.

The question is whether the bill as proposed can pass and whether it will have the intended impact. Both questions have uncertain answers.

UCLA urban planning professor Paavo Monkkonen believes that the bill can pass, but Schweitzer has warned that the bill would not muster support from low-income communities without some guarantees of affordable housing. While the bill does not override local laws regulating social housing and demolitions, progressives and low-income community groups find the status quo intolerable and demand additional protections. So far, there have not been endorsements in either direction from any elected representatives in poor or working-class urban areas. Instead, the support has come from people representing diverse middle-class areas: the three sponsors in the state legislature, and San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo.

Another potential pitfall involves commercial development. While most TOD today consists of apartment buildings, middle-class residents who choose to depend on public transportation need more than just a place to live and transit access to work.

Walkable urban neighborhoods with low car ownership have ground-level retail on their major arterial streets, with supermarkets, restaurants, clothing stores, hair salons, and other commercial establishments. The shopping experience in cities where most of the middle class does not own cars, such as New York or Paris, is different from the shopping experience of auto-oriented cities like Los Angeles, featuring big-box stores and strip malls. SB 827 makes it easy to redevelop these strip malls and parking lots as housing but says nothing about redeveloping them as walkable retail. On the contrary, the bill specifically restricts its attention to housing.

Even if the bill passes, cities that wish to only follow it to the letter may find ways around it. Areas that control their own local public transportation may reduce bus frequency below the 15-minute minimum threshold, and refrain from building rail extensions. To a large extent, many of those areas already oppose public transit, but NIMBY neighborhoods in Los Angeles and San Francisco that are not especially anti-transit today could become so in the future. One YIMBY on Twitter also notes that Aaron Peskin, a San Francisco Board of Supervisors member known for his opposition to new development, is trying to designate large swaths of his high-income district as a historic area, in which demolitions are not permitted.

SB 827 has a long route ahead of it. While it can certainly pass, and would have a positive effect on public transit and on housing affordability, it would almost certainly have to come with significant modifications. Some, concerning social housing mandates, would probably be required to obtain more support outside the YIMBY community, which is racially diverse but largely middle-class. Others are technical improvements to the bill's merits, such as retail TOD and some restrictions on cities' ability to abuse the historic overlay process to defeat the bill's intent. It's still early to tell what will come of this: as Schweitzer said, this is an opening salvo.

Alon grew up in Tel Aviv and Singapore. He has blogged at Pedestrian Observations since 2011, covering public transit, urbanism, and development. Now based in Paris, he writes for a variety of publications, including New York YIMBY, Streetsblog, Voice of San Diego, Railway Gazette, the Bay City Beacon, the DC Policy Center, and Urbanize LA. You can find him on Twitter @alon_levy.