Earlier this week, Urbanize ran a story about an unsolicited proposal from Fluor Enterprises to convert the Orange Line from a dedicated busway to a light rail line. Fluor, which also spearheaded the Eagle P3 project in Denver, proposes to accelerate the scheduled conversion from Metro’s planned late-2050s delivery, although specifics are currently unavailable.

The merits of the project itself are beside the point. Metro has money set aside for it, and, eventually, the Orange Line will become a part of the rail network. Fluor’s proposal does, however, provide an opportunity for Metro and the city of Los Angeles to work concertedly toward a mutually-held goal of increasing residential density near transit.

Metro, seeking to increase the county’s transit share to 25%, is generally shut out of land use decisions. The hurdles of establishing local funds for transportation projects usually leave the MTA with a weak hand to make demands of the communities through which its infrastructure will extend. In order to achieve support of two-thirds of the voters, Metro has continually handed over more discretion to city politicians, whose opposition on any given point could jeopardize regional plans for transit expansion.

The city of Los Angeles, fresh off a successful campaign to halt Measure S, must return to its efforts to build 100,000 new housing units by 2020. Indeed, even though such a goal is ambitious given the entrenched opposition to new development in much of the city, Los Angeles needs to be setting higher targets for the decade ahead. One of the central themes of the Measure S debate was the proliferation of so-called spot zoning, the determination of a project’s acceptability independent of the planning framework which is supposed to govern development in its vicinity. For better or worse, this tactic has likely taken hold as a direct result of the serial downzonings of the 1970s and 80s, and the failure of the community plan process to provide for sufficient upzonings where they are merited.

The Orange Line, which passes primarily through neighborhoods of single-family houses, provides an opportunity for Metro and Los Angeles to advance their respective goals. San Fernando Valley boosters have become vocal about their desire to see the Orange Line converted to rail. The enthusiasm for public transit is a welcome change, but it has not yet extended to a willingness to see the suburban character of the area change. Even in comparatively-dense North Hollywood, projects that would replace dead zones with new apartments are opposed for disturbing the “characteristics of existing neighborhoods.”

To recap, the Valley wants rail, but they don’t want density. Los Angeles wants to plan for density near transit, rather than risking the ire of residents by approving projects on a case-by-case basis. Metro wants to get the most out of its capital expenditures and increase ridership. Let’s compromise.

There is not a compelling reason to replace the Orange Line busway with rail today. If necessary, Metro can wait until the 2050s when its investment in the right-of-way will be half a century old. The argument, aside from the conferred status of a rail line, hinges upon the crowdedness of the buses. But bus ridership, here as elsewhere, has been listless for years. The narrative that the Orange Line is outgrowing its capacity is simply untrue, evidenced most recently by Metro’s projections that Bus Rapid Transit on Vermont would attract three times as many riders without the benefit of being fully separated from car traffic.

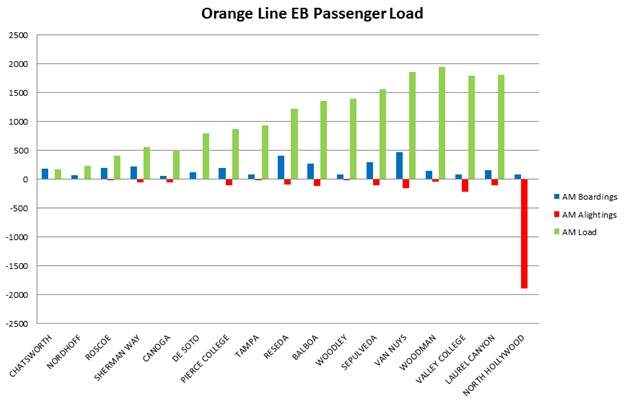

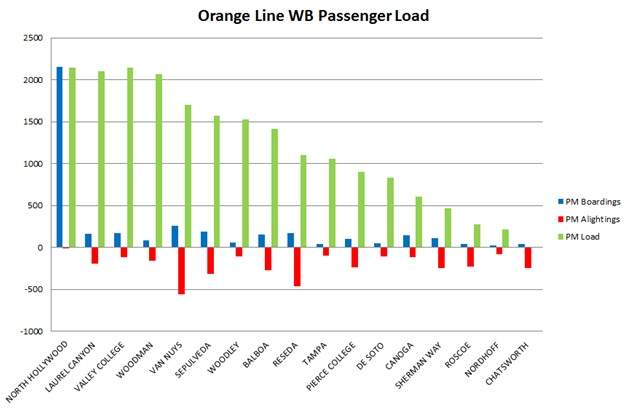

As has been noted elsewhere, the capacity of the line has been limited by political decisions, which should be reversed by the Department of Transportation. Operations will also be aided by the implementation of additional grade separations along the route, which should allow for more frequent service without the attendant bunching. The observed crowdedness really reflects the way that the line is used by passengers, which can be seen in Metro’s on/off data.

This dataset covers the peak hours of 6-9 AM and 4-7 PM, during which time about 55 percent of boardings on the line occur. Nearly 60 percent of passengers are riding the line to North Hollywood, where they can connect to the Red Line. Even though most stops generate few boardings, with this travel pattern, it’s pretty clear why the buses are crowded by the time they hit a busy transfer station at Van Nuys.

But this chart also highlights a key reason why the Orange Line would struggle to find success as a light rail line: very little of this traffic is native to the route. The bus is crowded not because so many people are using it, but because of how they are using it. The Valley is a vast area, and transit crossings over the hill are in short supply. The Orange Line’s success comes primarily from its function as a convenient and reliable cut-through route to get to Metro’s rail network. But, since the passengers don’t originate along the route, that also means that the service capacity could be augmented, as Henry Fung mentioned, by improving bus infrastructure elsewhere (on Ventura, for example) for less money.

Another factor to consider is the impact that the opening of the Sepulveda Line will have on the prevailing travel pattern here. By opening another route into the Los Angeles basin, riders will have an opportunity to self-sort based on their destination, and average trip length (the contributing factor to crowdedness) should decline on the Orange Line. With the Sepulveda Line assuming some significant portion of the trips currently occuring on Van Nuys buses, many of those riders will bypass the Orange Line altogether for a connection east or west at the Purple Line. In short, the segment of the Orange Line that currently experiences crowding, east of Van Nuys, actually figures to become less crowded without a rail conversion. Given the development patterns in the area, there is no reason to seek to funnel more cut-through traffic onto this specific route, when reliable bus connections to the Red and Sepulveda Lines could just as well be fostered at other points. The latter track makes more sense. So long as the city doesn’t permit apartments near the majority of the Orange Line’s route, there will always be a low ceiling on its potential ridership.

But, then, there’s this offer on the table. If the Fluor proposal is approved by the Office of Extraordinary Innovation, Metro could opt to move forward with the conversion early. Miles and miles of single-family houses will make for a lightly-used train line that will nonetheless greatly increase the property values of the homeowners nearby. So hopefully, if there is community support behind bringing rail back to the San Fernando Valley, Metro and city officials can first work together to turn that into support for a new dense corridor in the Valley.

Scott Frazier is a graduate student at Cal State University Los Angeles in Public Administration. Follow him on Twitter @safrazie.