Los Angeles is in the midst of an ambitious expansion of its rail network. Among the most intriguing projects in this transit buildout is the proposed run-through tracks at Union Station, called Link US. Approved two months ago, the $2.75-billion project will reconfigure the current stub-end layout of the station, allowing for through routing by 2024. The existing layout doesn't allow any through-service, so every Metrolink commuter line runs between Union Station and an outlying destination. Urbanize has covered this topic, focusing on construction options. But it's important to also think about the service plan: which trains will go where, at what frequency, and how they will interact with local transit service.

In Switzerland, transportation planners have a slogan: “electronics before concrete.” In Germany, rail activists have expanded on this to say “organization before electronics before concrete.” What this means is that it's expensive to pour concrete—to dig tunnels or build viaducts. It's less expensive to invest in better signaling and electrification. Improving organization—getting different agencies to work together, and running passenger-friendly service—requires no capital funding at all. Link US is an expensive investment, so public transportation advocates must think about how to optimize organization and electronics to ensure the region will get its money's worth of good service.

As far as electronics goes, the region needs to electrify as much of its commuter rail system as possible. Paul Dyson, of the advocate group RailPAC, has proposed a starter system called Electrolink, which would electrify the Antelope Valley and Orange County Lines, producing a northwest-to-southeast trunk line for both high-speed trains and slower commuter trains. This is similar to the post-electrification setup for Caltrain, the so-called blended plan with high-speed rail.

One way to extend Electrolink would be to incorporate the inner Ventura County Line. While Union Pacific objects to electric service, Metrolink owns part of the corridor, and if negotiations reach an impasse, it could build its own tracks.

Organization means using regional rail to provide integrated service connecting the Valley, Downtown Los Angeles, and Orange County. This requires fare integration: a trip between Burbank and Downtown should cost the same no matter whether the passenger rides a direct bus, or rides a bus and connects to the Red Line, or takes Metrolink. This is unheard of in the United States, but is routine in most of Europe. A zoned ticket in a German-speaking city, or a monthly ticket in the entire Paris region, is valid on all public transit options. In contrast, a Metro Rail or bus fare is $1.75 one-way, whereas Metrolink charges $3.75 from Burbank to Union Station and $6 from Sylmar.

Organization also means running more frequent service. When service is frequent at all times of day, people use it at all times of day. In major European cities like Paris, Munich, and Berlin, individual commuter rail branches run every 10, 15, or 20 minutes all day. Los Angeles may not have as large of a transit system, but it is a bigger city than all three combined. When Link US opens, Metrolink should plan on running trains on each branch every 10 or at worst 15 minutes even outside rush hour; at rush hour, it can run additional service.

Organization and electronics then interact positively, in the form of infill stops. Today, stop spacing on Metrolink is very wide. Sylmar, the fourth stop on the Antelope Valley Line, is 21 miles from Union Station. Chatsworth, the sixth stop on the Ventura County Line, is 29 miles away. Fullerton, the fifth stop on the Orange County Line, is 23 miles away. In the major European cities, a stop every mile or two is more normal. There are three reasons for this discrepancy:

- Metrolink's diesel trains accelerate more slowly than electric trains (so slow that area advocate Paul Druce found large speed gains coming from electrification), so a tight stop spacing would slow them down more.

- Metrolink's premium fares discourage ridership from closer in, and encourage ridership by high-income drivers, who drive long distances to a park-and-ride.

- In systems with fare integration, there is value to putting stops at the intersections with the busiest bus and local rail corridors.

All three issues could be resolved if Metrolink established the Electrolink program in conjunction with Link US, and integrated fares properly. Riders from the Valley would want to take the train into Downtown for work; even some trips to the Westside would be faster with a connection between Metrolink and the Purple Line than a direct bus trip.

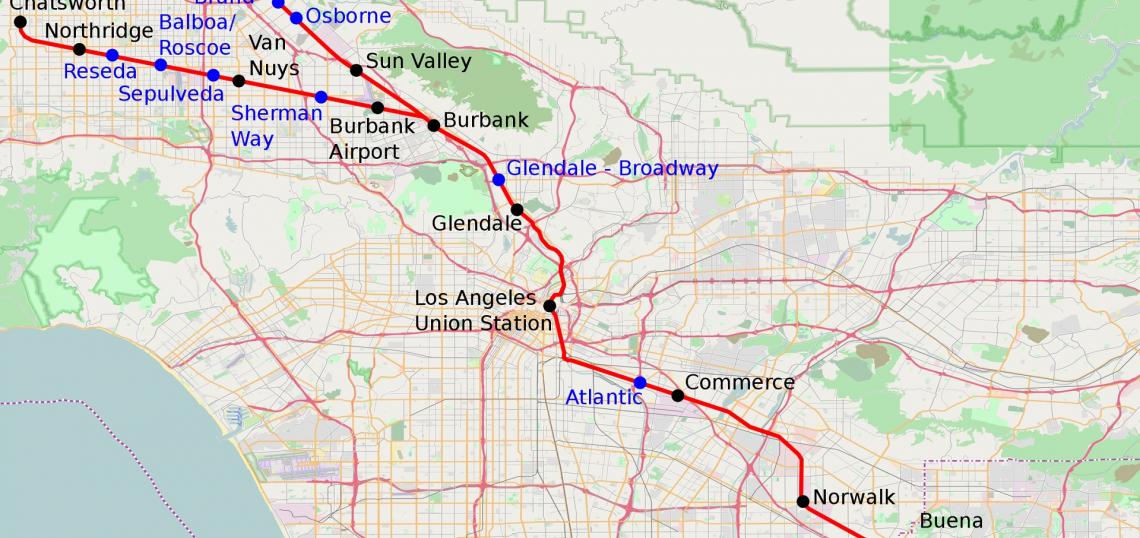

This means that there should be infill stations at the major bus corridors, on both the Ventura County and Antelope Valley Lines. The Ventura County Line could get stops at Sherman Way, Sepulveda, Roscoe/Balboa, and Reseda. The Antelope Valley Line could get a stop at Broadway in Glendale, meeting a potential Orange Line extension to Pasadena, and additional stops in the Valley, such as at Osborne, Van Nuys, and Brand. On the Orange County Line, infill stops are harder and less useful, because the land use near the stations is entirely industrial, and there are fewer good bus transfers, but the line could still open a new stop at Atlantic.

The northwest-to-southeast Electrolink trunk would provide a fast, frequent transportation artery to the Valley and parts of Orange County. It would be like an entirely new Metro Rail line. The changes it would cause to travel patterns in the areas it served make it worthwhile to examine where Los Angeles County should spend the rest of its capital budget, and how.

With better Metrolink service, it is best to prioritize rail access to areas far from Metrolink. Los Angeles was a small city in the second half of the 19th century, when New York and Chicago built their vast rail networks, radiating in every direction from their centers. This means large swaths of the region are far from mainline rail; they developed around the Pacific Electric streetcars or the automobile. These include the Westside, South Bay, and South Los Angeles; the South Vermont corridor is far from any mainline rail. In contrast, new rail extensions that parallel Metrolink lines, such as Measure M's West Santa Ana Branch, deserve a lower priority.

In areas near Metrolink, it is better to invest in small rail and bus projects that connect to commuter trains. This includes extending the Orange Line to Burbank and Pasadena, and the Green Line to the Norwalk Metrolink station. Both of these projects are already on the Measure M list, but better Metrolink service would make them more useful, and deserving of higher priority.

The most effective integrated transportation planning considers all public transit options together. The cities with the best public transit aim to give passengers a seamless experience, no matter what kind of vehicle they take—bus, light rail, subway, or commuter rail—and how many transfers they make. But they also plan all of these different modes of public transit together, and aim for complementary rather than competing service.

In the middle of the next decade, Metrolink will have the infrastructure for a subway-like commuter rail system, if it makes investments much smaller in scope than Link US. The county should take advantage of this situation and make the required changes, not just to Metrolink but also to the other rail lines that it is planning.

Alon grew up in Tel Aviv and Singapore. He has blogged at Pedestrian Observations since 2011, covering public transit, urbanism, and development. Now based in Paris, he writes for a variety of publications, including New York YIMBY, Streetsblog, Voice of San Diego, Railway Gazette, the Bay City Beacon, the DC Policy Center, and Urbanize LA. You can find him on Twitter @alon_levy.