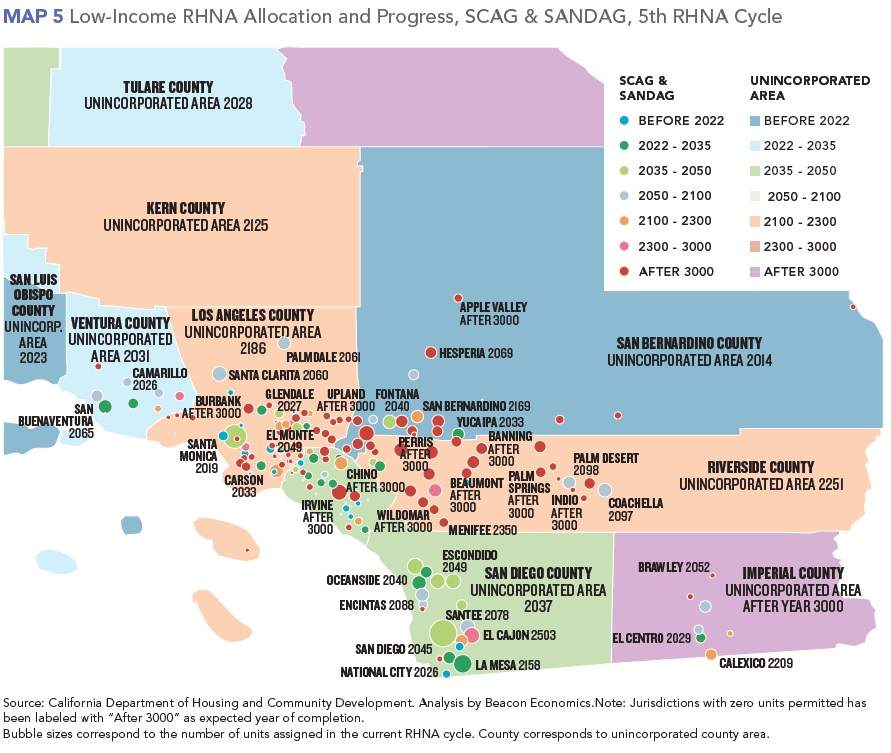

A new study from Beacon Economics and the thinktank Next 10 finds that many California cities - including those in Los Angeles County - are falling behind on their low-income housing production targets.

The report, called "Missing the Mark: Examining the Shortcomings of California's Housing Goals," examines the progress made by California's 539 jurisdictions toward meeting their regional housing needs assessment goals. The RHNA, which is updated every five to eight years, sets the amount of housing that each city is expected to permit per cycle.

“This data shows that state-wide, less than 10 percent of the RHNA-allocated low- and very-low income units have been permitted, compared to nearly half of the higher-income housing,” said F. Noel Perry, businessman and founder of Next 10 in a statement. “This disturbing trend reveals how little is being done to alleviate the affordability crisis in California, contributing to rising homelessness and displacement across the state.”

The analysis by Next 10 and Beacon found that not only do most cities fail to permit a sufficient amount of housing, but that 100 of the state's 539 jurisdictions have neglected to even report their progress. Of those 100 jurisdictions, 20 are located in Los Angeles County, including El Segundo, Hermosa Beach, Compton, Pomona, and Azusa.

Statewide, less than 26 percent of the required state-wide units have been permitted, despite the fact that the current RHNA cycle is already past its halfway point. This includes approximately 45 percent of required above moderate-income units, 19 percent of required moderate-income units, less than 10 percent of required low-income units, and just over 7 percent of required very low-income units.

Perhaps most glaringly, at the current pace of permitting, many jurisdictions will take decades - or even centuries - to reach their current housing goals.

The cities of Los Angeles and Long Beach are on pace to reach their current low-income housing goals near the year 2040.

But compared to Burbank, the County's two largest jurisdictions are good actors. Burbank, at its current pace of permitting, would not meet its low-income housing goal until after the year 3000.

“RHNA was established fifty years ago to ensure communities were building housing across all economic segments,” said Adam Fowler, director of research at Beacon Economics. “However, the program has no meaningful enforcement mechanism and many jurisdictions simply aren’t participating. But this is only part of why RHNA has proven to be an inefficient tool to ensure supply keeps up with demand.”

The report also concludes that the RHNA goals themselves have proven to be a flawed metric, with certain jurisdictions able to earn high grades by placing low targets.

“If Beverly Hills can get an A because they built all three of the units allocated to them over an eight-year period, despite being forecasted to add an estimated 300 households and 3,400 jobs by 2020, you begin to get a sense that the targets themselves are part of the problem,” said Fowler.

Moving forward, the report recommends that California should redefine how it calculates its housing needs and better align its goals with projected regional housing growth. It also recommends that local zoning laws that discourage multifamily developments in favor of single-family homes should be revised.

The latter recommendation is subject to several legislative efforts at the state level, including San Francisco Senator Scott Wiener's SB 50 - which would allow for the construction of apartment buildings near transit stations and near job centers, even when disallowed by local zoning regulations.